Polarisation and partisanship: 10 key takeaways from our World Values Survey conference

Hundreds joined the conference at King’s College London’s Bush House.

On Thursday 11 April 2024 around 200 people joined the Policy Institute for a major international academic conference in London which saw 40 researchers from 15 countries present their findings and insights on polarisation and partisanship – among the key political challenges of our time. Here are 10 key insights from the day’s proceedings.

1. The recent success of right-wing populist parties may not be linked to increasing polarisation and decreasing levels of trust

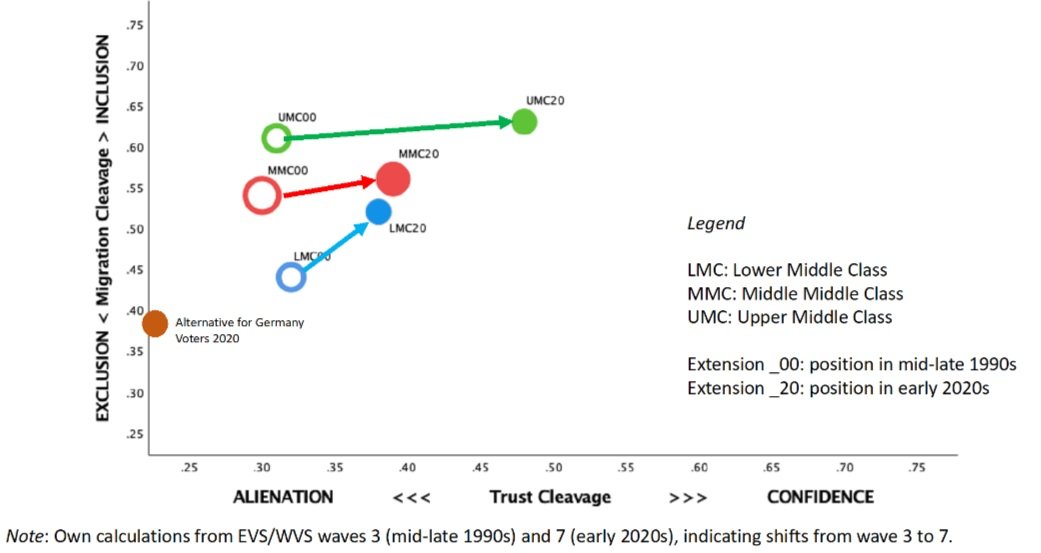

Prof. Christian Welzel debunked the relationship between polarisation in values and levels of institutional trust in his keynote presentation, arguing the recent successes of right-wing populist parties across Europe cannot be linked to ideological changes.

He showed how, across issue divides (such as economic values, immigration, and diversity), there has been little movement been socioeconomic groups, and in many cases institutional trust is increasing rather than decreasing.

Rather, he suggests the success of right-wing populism may be related to the changing structures of political parties across Europe, and how new parties are able to interact with the electorate via the increased role of social media. Welzel made the point that this is primarily a supply problem rather than a demand issue from the electorate, where populist parties are filling a gap left by mainstream parties, which are increasingly made up of highly educated “elites”.

In Germany trust has increased across socioeconomic groups, and there has been a shift towards more inclusive attitudes to immigration

2. Party fragmentation may not directly lead to increasing levels of polarisation in many Western democracies, with the US being an exceptional case

For our other keynote address, Prof. Pippa Norris further suggested that the degree of contemporary party polarisation in the US may be exceptional compared to other Western democracies. While party fragmentation – the share of parties in the electorate or parliament – has increased across Western democracies, this is not a proxy for the level of polarisation within a party system (the difference in left-right or liberal-conservative attitudes between parties).

The ideological position of political parties across most Western democracies remains balanced between left-right and liberal-social values, and the overall degree of party system polarisation in the US is remarkably different to most other Western democracies.

Norris noted how exceptional many of the features of the US political system are, and how we should be cautious in generalising to other democratic nations, as the chart below illustrates.

The US is an exceptional outlier when it comes to the level of polarisation between political parties on economic and social issues

3. A multidimensional understanding of a population's values might help us to explain the phenomenon of negative partisanship

Prof. Paula Surridge reflected on the puzzle around negative partisanship – the tendency for people to form political opinions primarily in opposition to parties and groups they dislike – and how this has risen in many places, despite decreasing partisanship more generally. Multidimensional understandings of an individual’s political ideologies are key, she said, highlighting how it may be difficult to find a home for the complex positions the electorate hold within current political systems.

4. Modern politics is increasingly messy – yet multi-party systems might help to curb the negative impacts of polarisation

Prof. Anand Menon reflected on the messy nature of modern politics, and the striking degree of polarisation held within parties. He focused on how some aspects of polarisation can be positive, allowing the electorate to make distinctions between political parties and often increasing political engagement. He advocated for the benefits of multi-party systems, on the basis that they can force political parties to engage with a diverse range of values and attitudes, curb threats from far-right extremist parties when they get to power, and foster a stronger collaborative focus on society's long-term challenges.

5. Policymakers and academics should increasingly use the World Values Survey to find regional variations in values, and to find common values

David Halpern commented on the critical role of studies like the World Values Survey and the European Values Study in allowing researchers to gain stronger perspectives on global trends in values and attitudes. He emphasised that many countries exhibit strong regional variation in values, with a complex web of alignment both within and across regions: his research shows how the North of England, for example, has far more similar values to (former) East Germany than to the South of England. He emphasised that the WVS allows policymakers and researchers to make strong regional comparisons between countries, and understand where opportunities may arise from shared global perspectives across issues.

6. Issue polarisation has a negative impact within societies, and can lead to affective partisan sorting

Where issues do cause a level of polarisation between groups, it can have serious negative effects. Results from a study by Ugur Ozdemir (A Dividing Nation? Elections, referenda and affective partisan sorting in the UK), indicate that affective polarisation in the UK has become more clearcut over time, with stronger emotional hostility between partisan groups. With opinion-based issues fuelling affective polarisation, there is a concern that the divide between polarised partisan groups may become greater in the future.

The level of affective partisan sorting has increased across England, Scotland and Wales from 2014-2023 – with a sharp increase in England and Wales after the Brexit referendum

7. Understanding the specific global contexts in which polarisation occurs is important to accurately understand its problems and effects

Across all our panels, in-depth discussions were held on the contextual nature of polarisation, and how generalisations made between countries can often result in misleading findings. US exceptionalism was commonly noted, with the level and relationship of polarisation varying across issues and geographical space.

Findings on age, period and cohort trends showed significant cross-regional variation in the level of support for alternative forms of non-democratic government, especially with large overall increases in Latin America. It revealed how the youngest cohorts (Millennials and Gen Z) may be experiencing increased support for alternative forms of government in some parts of the world. However, differences between cohort effects are smaller across most countries compared with the US. Researchers emphasised the need to pay close attention to the specific background and context within countries and avoid making global claims around issues.

Support for having a strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with rules or parliament is rising in many parts of the world, especially in the US, Africa and Latin America, with younger generations notably more supportive in some countries, particularly the US

8. Social attitudes are emerging as the main diving factor – both within countries and across the world

Prof. Bobby Duffy highlighted how social values are shifting across much of the world. There has been significant liberalisation in attitudes in many nations, particularly in Europe, North America and Oceania – but this has not been seen in Africa and Asia to the same degree. We can sometimes trip into the misperception that we are coming together on these issues, when the real pattern is a global divergence between many regions on social issues since the 1980s. The WVS allows for these long-term international comparisons, reminding us that polarisation is not just a national phenomenon, but that country dispersion in time also adds to global tension.

Many countries in Europe, the Americas and Oceania have become more socially liberal since the 1980s – but other nations in Africa and Asia have seen slower or little change

9. The UK is not the US: while some level of polarisation is being experienced within the UK, it is nothing compared to the level of division seen in the United States

Multiple findings emphasised the need to consider the relative levels of polarisation being experienced across different contexts. In his opening remarks, Prof. Bobby Duffy highlighted how the level of difference in traditional and liberal attitudes between supporters of the two main parties is significantly higher in the US compared to Great Britain. There was, in fact, very little partisan polarisation in the US in 1990, but over time, this gap has widened significantly, while in Great Britain the main trend has been a liberalisation in attitudes among both groups – although we may be seeing some nascent polarisation. This will be a key trend to monitor in Britain in future WVS waves.

The level of polarisation in social attitudes between Democratic and Republican supporters has grown hugely in the US since the 1990s, though this is not a trend mirrored between Labour and Conservative supporters in Great Britain

10. Polarisation needs to be defined as a multidimensional problem, made up of several (often competing) differences in values, attitudes and beliefs

Polarisation should be understood as a wide-ranging issue, and in order to investigate it, researchers should assess divides across a wide range of social issues and differences in values. Lee de Wit presented a new approach to measuring issue polarisation (Towards a clustering-based measure of issue polarisation) using k-means cluster analysis to classify polarisation across multiple question areas and multiple countries. This novel measure of polarisation has strong consistency with other metrics of polarisation, and shows the largest and most consistent disagreement between groups is based around cultural issues such as abortion, homosexuality and prostitution.

The largest and most consistent disagreement between clusters of respondents are around cultural issues, such as abortion, homosexuality and prostitution

Novel qualitative approaches can also be used to explore public values in more depth and add more context to how issues drive major differences between groups. John Postil presented new ethnographic evidence (Follow the (de)polarisers: anthropological notes on the global culture wars) exploring how researchers might use online evidence to follow the role of various actors within polarising debates. His presentation raised the importance of understanding the interactions between polarisers and de-polarisers within debates, and identifying how certain individuals straddle both sides of a divided topic.